Norman Doige writes in The Tablet A startling investigation into how a cheap, well-known drug became a political football in the midst of a pandemic. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Norman Doige writes in The Tablet A startling investigation into how a cheap, well-known drug became a political football in the midst of a pandemic. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

We live in a culture that has uncritically accepted that every domain of life is political, and that even things we think are not political are so, that all human enterprises are merely power struggles, that even the idea of “truth” is a fantasy, and really a matter of imposing one’s view on others. For a while, some held out hope that science remained an exception to this. That scientists would not bring their personal political biases into their science, and they would not be mobbed if what they said was unwelcome to one faction or another. But the sordid 2020 drama of hydroxychloroquine—which saw scientists routinely attacked for critically evaluating evidence and coming to politically inconvenient conclusions—has, for many, killed those hopes.

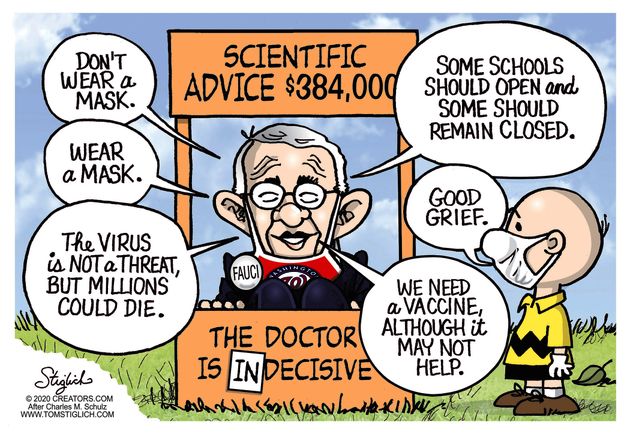

Phase 1 of the pandemic saw the near collapse of the credible authority of much of our public health officialdom at the highest levels, led by the exposure of the corruption of the World Health Organization. The crisis was deepened by the numerous reversals on recommendations, which led to the growing belief that too many officials were interpreting, bending, or speaking about the science relevant to the pandemic in a politicized way. Phase 2 is equally dangerous, for it shows that politicization has started to penetrate the peer review process, and how studies are reported in scientific journals, and of course in the press.

What is unique about the hydroxychloroquine discussion is that it is a story of “unwishful thinking”—to coin a term for the perverse hope that some good outcome that most sane people would earnestly desire, will never come to pass. It’s about how, in the midst of a pandemic, thousands started earnestly hoping—before the science was really in—that a drug, one that might save lives at a comparatively low cost, would not actually do so. Reasonably good studies were depicted as sloppy work, fatally flawed. Many have excelled in making counterfeit bills that look real, but few have excelled at making real bills look counterfeit. As such, as we sort this out, we shall observe not only some “tricks” about how to make bad studies look like good ones, but also how to make good studies look like bad ones. And why should anyone facing a pandemic wish to discredit potentially lifesaving medications? Well, in fact, this ability can come in very handy in this midst of a plague, when many medications and vaccines are competing to Save the World—and for the billions of dollars that will go along with that.

So this story is twofold. It’s about the discussion that unfolded (and is still unfolding) around hydroxychloroquine, but if you’re here for a definitive answer to a narrow question about one specific drug (“does hydroxychloroquine work?”), you will be disappointed. Because what our tale is really concerned with is the perilous state of vulnerability of our scientific discourse, models, and institutions—which is arguably a much bigger, and more urgent problem, since there are other drugs that must be tested for safety and effectiveness (most complex illnesses like COVID-19 often require a group of medications) as well as vaccines, which would be slated to be given to billions of people. “This misbegotten episode regarding hydroxychloroquine will be studied by sociologists of medicine as a classic example of how extra-scientific factors overrode clear-cut medical evidence,” Yale professor of epidemiology Harvey A. Risch recently argued. Why not start studying it now?

Norman Doige tells the story in some detail (see article link in red at the top)

- the history of quinine, chloroquine, and HCQ medical effectiveness;

- how HCQ was used against SARS CV2 early on;

- how Raoult was the one in his lab who came up with the idea of combining the two older drugs, HCQ and azithromycin, for COVID-19;

- the criticisms of the French studies exemplifying “unwishful thinking”;

- Trump’s interest in HCQ and the media backlash against the medicine;

- the failure of ICU treatment protocols with ventilators and no alternatives to off-label prescribing;

- the insistence upon Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) as the only valid test for HCQ;

- the confounding factors in such studies and the problems replicating RCT results; and,

- the publication in high-profile journals of studies structured for HCQ to fail to help infected patients.

Conclusion from Doige

Lots and lots of COVID-19 studies will come out—several hundred are in the works. People will hope more and more accumulating numbers—and more big data—will settle it. But big data, interpreted by people who have never treated any of the patients involved can be dangerous, a kind of exalted nonsense. It’s an old lesson: Quantity is not quality.

On this, I favor the all-available-evidence approach, which understands that large studies are important, but also that the medication that might be best for the largest number of people may not be best one for an individual patient. In fact, it would be typical of medicine that a number of different medications will be needed for COVID-19, and that there will be interactions of some with patient’s existing medications or conditions, so that the more medications we have to choose from, the better. We should be giving individual clinicians on the front lines the usual latitude to take account of their individual patient’s condition, and preferences, and encourage these physicians to bring to bear everything they have learned and read (they have been trained to read studies), and continue to read, but also what they have seen with their own eyes. Unlike medical bureaucrats or others who issue decrees from remote places physicians are literally on our front lines—actually observing the patients in question, and a Hippocratic Oath to serve them—and not the Lancet or WHO or CNN.

As contentious as this debate has been, and as urgent as the need for informed and timely information seems now, the reason to understand what happened with HCQ is for what it reflects about the social context within which science is now produced:

- a landscape overly influenced by technology and its obsession with big data abstraction over concrete, tangible human experience;

- academics who increasingly see all human activities as “political” power games, and so in good conscience can now justify inserting their own politics into academic pursuits and reporting;

- extraordinarily powerful pharmaceutical companies competing for hundreds of billions of dollars;

- politicians competing for pharmaceutical dollars as well as public adoration—both of which come these days too much from social media; and,

- the decaying of the journalistic and scholarly super-layers that used to do much better holding everyone in this pyramid accountable, but no longer do, or even can.

If you think this year’s controversy is bad, consider that hydroxychloroquine is given to relatively few people with COVID-19, all sick, many with nothing to lose. It enters the body, and leaves fairly quickly, and has been known to us for decades. COVID vaccines, which advocates will want to be mandatory and given to all people—healthy and not, young and old—are being rushed past their normal safety precautions and regulations, and the typical five-to-10-year observation period is being waived to get “Operation Warp Speed” done as soon as possible.

This is being done with the endorsement of public health officials—the same ones, in many cases who are saying HCQ is suddenly extremely dangerous.

Philosophically, and psychologically, it is a fantastic spectacle to behold, a reversal, the magnitude and the chutzpah of which must inspire awe: a public health establishment, showing extraordinary risk aversion to medications and treatments that are extremely well known, and had been used by billions, suddenly throwing caution to the wind and endorsing the rollout of treatments that are entirely novel—and about which we literally can’t possibly know anything, as regards to their long-term effects. Their manufacturers know this well themselves, which is why they have aimed for, insisted on, and have already been granted indemnification—guaranteed, by those same public health officials and government that they will not be held legally accountable should their product cause injury.

From unheard of extremes of caution and “unwishful thinking,” to unheard of extremes of risk-taking, and recklessly wishful thinking, this double standard, this about-face, is not happening because this issue of public safety is really so complex a problem that only our experts can understand it; it is happening because there is, right now, a much bigger problem: with our experts, and with the institutions that we had trusted to help solve our most pressing scientific and medical problems.

Unless these are attended to, HCQ won’t be remembered simply as that major medical issue that no one could agree on, and which left overwhelming controversy, confusion, and possibly unnecessary deaths of tens of thousands in its wake; it will be one of many in a chain of such disasters.

Norman Doidge, a contributing writer for Tablet, is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and author of The Brain That Changes Itself and The Brain’s Way of Healing.