Joel Kotkin writes at Real Clear Energy The Green Civil War. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and images.

Like many contemporary social movements—#metoo, Black Lives Matter, the Women’s March—the environmental lobby has tended to create an atmosphere of unanimity. In its struggle to win public and elite opinion, it has frequently evoked “science” as something settled and immutable, warning that those who dissent are either self-serving or seriously deranged.

Yet in recent months, there has been growing criticism about the current green orthodoxy, including from people long associated with environmental causes. This has been most widely seen in the strange case of the Michael Moore–produced Planet of Humans, which exposes the rapacious profit-seeking and gratuitous environmental damage caused by the renewable energy industry.

Critics have attempted to get Moore’s film de-platformed, and the green establishment has pressured distributors not to take the film. Such censorious behavior is increasingly common among the greens. Some veteran climate scientists—such as Roger Pielke and Judith Curry, Greenpeace founder Patrick Moore, and former members of the UN International Panel on Climate Change—have been demonized and marginalized for deviating from what Curry has described as an overly “monolithic” approach to the issue of climate change. Some political leaders even seem ready to take dissenters to court in an effort to ban their ideas by legal means. Not only energy companies but think tanks and dissident scientists have been targeted for criminal prosecution. These tactics are all too reminiscent of the medieval Inquisition.

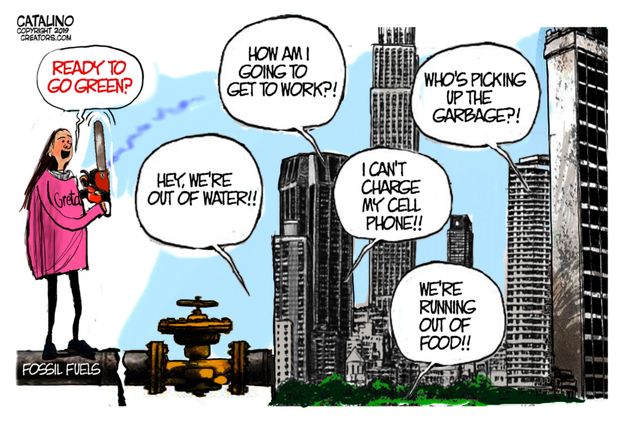

The Green War on the Working Class

Moore’s apostasy may be better known but lacks the breadth of Michael Shellenberger’s new book, Apocalypse Never. A green zealot from his high school years, the Berkeley-based Shellenberger has worked on protecting habitats for endangered species and has battled climate change. His book, like Moore’s movie, exposes the hypocrisy of the green elite but, importantly, offers a more hopeful approach than Moore’s Malthusian worldview.

Like Moore, Shellenberger has become utterly disillusioned with the self-serving and often counterproductive policies pushed by the green lobby. He demonstrates how green policies backed by oligarch-funded nonprofits have often worked against the economic interests of people in Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America, often leaving them with little recourse but to pillage their own natural environments.

Shellenberger blasts green nonprofits for blocking new energy development—dams, gas plants, pipelines—in these countries. Such actions may seem noble enough to the rich of the West, but it slows the manufacturing growth that could allow these countries to become rich enough to accommodate such things as habitat preservation. People working in textile or garment plants need not rely on the jungle for their survival, reducing the need to consume its bounty.

“Rainforests in the Amazon and elsewhere in the world can only be saved if the need for economic development is accepted, respected, and embraced,” Shellenberger states. “By opposing many forms of economic development in the Amazon, particularly the most productive forms, many environmental NGOs, European governments, and philanthropies have made the situation worse.”

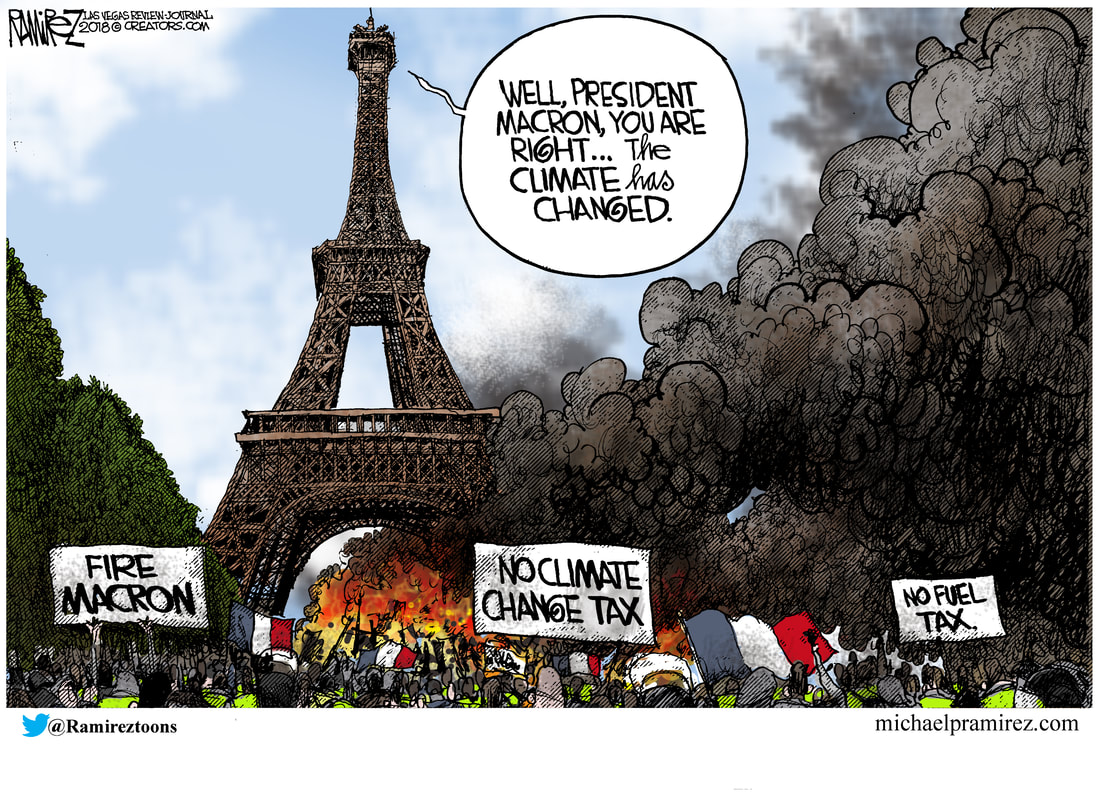

Green plans to raise energy prices, eliminate cars, and ban fossil fuel development also have stirred fierce opposition from the working class, whether in pro-Trump middle America, or among France’s gilets jaune. But it’s not just the proverbial angry white men. In California, some 200 local civil rights leaders have filed lawsuits against the state’s regulators, arguing that the state’s climate policies are essentially discriminatory toward poor people and minorities.

Challenging Religious Orthodoxy

Even before Black Lives Matter, mainstream American journalism was being transformed into an extended-stay resort for the woke. Shellenberger calls out “stealth environmental activists working as journalists” who report the most drastic environmental projections while ignoring any contrary perspectives. “Much of what people are being told about the environment, including the climate, is wrong, and we desperately need to get it right,” he insists, suggesting that he is “fed up with the exaggeration, alarmism, and extremism that are the enemy of a positive, humanistic, and rational environmentalism.”

Shellenberger places his hopes on “competition from outside traditional news media institutions,” having seen the gullibility of most reporters. For decades, they have embraced notions, first seen in Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 book, The Population Bomb, that humanity would “breed ourselves to extinction” if birthrates were not severely curtailed. Reporters also widely hailed the Club of Rome report in 1972, which took a similar apocalyptic approach, predicting massive shortages of natural resources unless there was a shift to lower birthrates, slower economic growth, less material consumption, and, ultimately, less social mobility.

Many of these apocalyptic predictions, like those in the Middle Ages, proved exaggerated or even plain wrong. Contrary to environmentalist dogma from the 1970s, natural resources, including energy and food, did not run out but became more available than anyone expected. So why the constant hyping and hysteria? Because what Shellenberger calls “the apocalyptic environmental tradition” demands it.

In a way that perhaps only someone bitten by the green bug could understand, Shellenberger labels environmentalism as “the dominant secular religion of the educated, upper-middle-class elite in most developed and many developing nations.” This applies, he reports, not only to seemingly deranged cults like Britain’s Extinction Rebellion but also to august environmental groups like the Sierra Club or Friends of the Earth. Christianity offered guidance for how one should live and conduct one’s personal affairs in a manner pleasing to God, but the green movement seeks to steer people toward a life in better harmony with nature.

Like medieval Catholicism, the green faith foresees impending doom caused by human activity; human sin was the primary reason for the world’s problems in medieval times, and has been rediscovered by environmentalists. “Apocalyptic environmentalism gives people a purpose: to save the world from climate change, or some other environmental disaster,” Shellenberger writes. “It provides people with a story that casts them as heroes“.”

Needed: A New Human-Centered Approach to the Environment

Perhaps what is most revolutionary about Shellenberger’s book is his call for a new, more human-centered, environmentalism. In contrast to the green movement’s jihad against material progress, he suggests that only by making people more affluent will they be able to afford the environmental redress that the planet, in fact, needs.

Rather than battle industrialism, greens need to appreciate what technological progress has done for the environment. The development of plastics helped reduce demand for ivory, hawksbill turtles, whale oil, and the despoiling of old forests. Dealing pragmatically, as opposed to religiously, with environmental concerns, means accepting the reality that some forms of efficient energy production, such as natural gas or nuclear, need to be part of a cleaner future. “It is only by embracing the artificial that we can save what’s natural,” he states.

The key to environmental success lies in affluence. “Richer countries are more resilient,” he says, quoting MIT climate scientist Kerry Emanuel, “so let us focus on making people richer and more resilient.” Countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and particularly Scandinavia become cleaner, in large part, because they can afford to do so and also must respond to popular pressures. Poor autocratic and officially socialist states, like those of the former Soviet bloc and China, did not face the same pressures for a cleaner environment.

In the future, to succeed, environmental policy has to consider human concerns, particularly those of the working and middle classes. It needs not only to “protect the natural environment but also to achieve the goal of universal prosperity.” Thus Shellenberger speaks of “a positive, humanistic, and rational environmentalism.” Like any movement in a still-democratic society, he suggests, environmentalists can win over the population not by terrorizing them but by showing that we can protect nature without stomping out all natural human aspirations.

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike