RAPID Array measuring North Atlantic SSTs.

For the last few years, observers have been speculating about when the North Atlantic will start the next phase shift from warm to cold. Given the way 2018 went and 2019 is following, this may be the onset. First some background.

. Source: Energy and Education Canada

An example is this report in May 2015 The Atlantic is entering a cool phase that will change the world’s weather by Gerald McCarthy and Evan Haigh of the RAPID Atlantic monitoring project. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

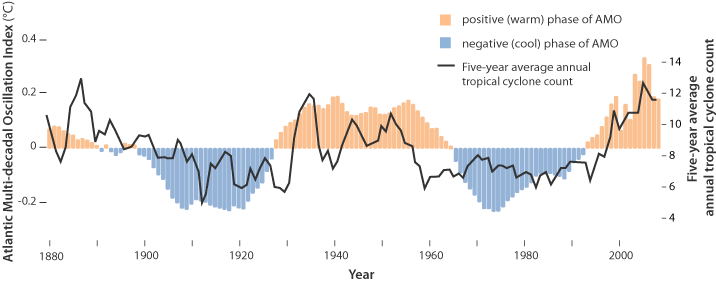

This is known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), and the transition between its positive and negative phases can be very rapid. For example, Atlantic temperatures declined by 0.1ºC per decade from the 1940s to the 1970s. By comparison, global surface warming is estimated at 0.5ºC per century – a rate twice as slow.

In many parts of the world, the AMO has been linked with decade-long temperature and rainfall trends. Certainly – and perhaps obviously – the mean temperature of islands downwind of the Atlantic such as Britain and Ireland show almost exactly the same temperature fluctuations as the AMO.

Atlantic oscillations are associated with the frequency of hurricanes and droughts. When the AMO is in the warm phase, there are more hurricanes in the Atlantic and droughts in the US Midwest tend to be more frequent and prolonged. In the Pacific Northwest, a positive AMO leads to more rainfall.

A negative AMO (cooler ocean) is associated with reduced rainfall in the vulnerable Sahel region of Africa. The prolonged negative AMO was associated with the infamous Ethiopian famine in the mid-1980s. In the UK it tends to mean reduced summer rainfall – the mythical “barbeque summer”.Our results show that ocean circulation responds to the first mode of Atlantic atmospheric forcing, the North Atlantic Oscillation, through circulation changes between the subtropical and subpolar gyres – the intergyre region. This a major influence on the wind patterns and the heat transferred between the atmosphere and ocean.

The observations that we do have of the Atlantic overturning circulation over the past ten years show that it is declining. As a result, we expect the AMO is moving to a negative (colder surface waters) phase. This is consistent with observations of temperature in the North Atlantic.

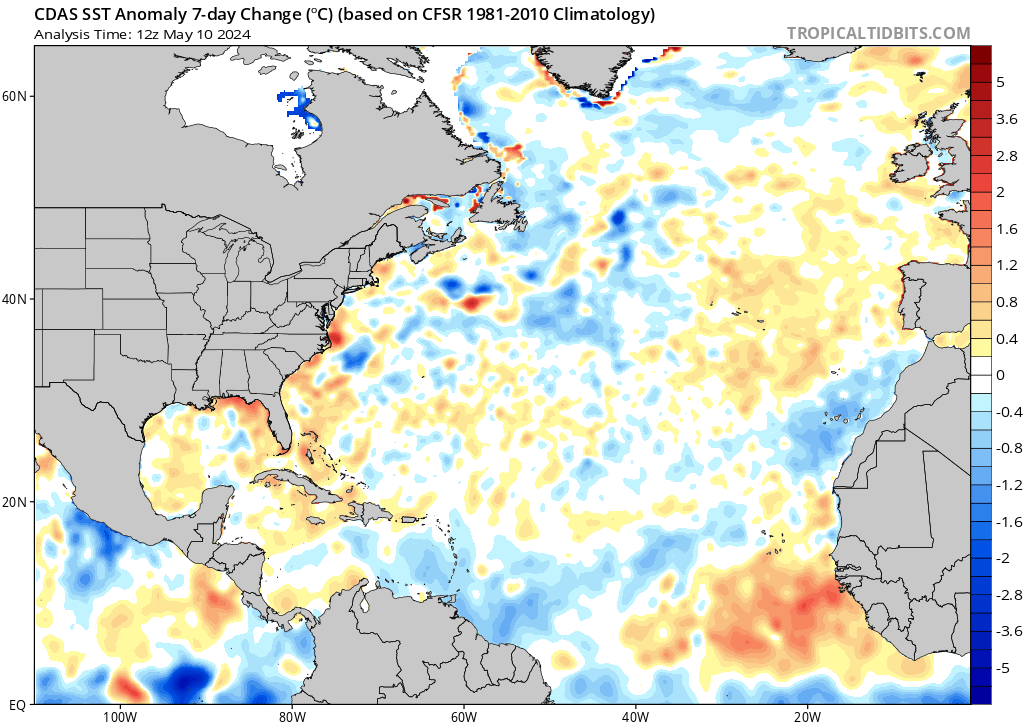

Cold “blobs” in North Atlantic have been reported, but they are usually winter phenomena. For example in April 2016, the sst anomalies looked like this

But by September, the picture changed to this

And we know from Kaplan AMO dataset, that 2016 summer SSTs were right up there with 1998 and 2010 as the highest recorded.

As the graph above suggests, this body of water is also important for tropical cyclones, since warmer water provides more energy. But those are annual averages, and I am interested in the summer pulses of warm water into the Arctic. As I have noted in my monthly HadSST3 reports, most summers since 2003 there have been warm pulses in the north atlantic.

The AMO Index is from from Kaplan SST v2, the unaltered and not detrended dataset. By definition, the data are monthly average SSTs interpolated to a 5×5 grid over the North Atlantic basically 0 to 70N. The graph shows the warmest month August beginning to rise after 1993 up to 1998, with a series of matching years since. December 2016 set a record at 20.6C, but note the plunge down to 20.2C for December 2018, matching 2011 as the coldest years since 2000.

October 2019 confirms the summer pulse weakening, along with 2018 well below other recent peak years since 2013. Because McCarthy refers to hints of cooling to come in the N. Atlantic, let’s take a closer look at some AMO years in the last 2 decades.

October 2019 confirms the summer pulse weakening, along with 2018 well below other recent peak years since 2013. Because McCarthy refers to hints of cooling to come in the N. Atlantic, let’s take a closer look at some AMO years in the last 2 decades.

This graph shows monthly AMO temps for some important years. The Peak years were 1998, 2010 and 2016, with the latter emphasized as the most recent. The other years show lesser warming, with 2007 emphasized as the coolest in the last 20 years. Note the red 2018 line was at the bottom of all these tracks. The short black line shows that 2019 began slightly cooler than January 2018, then tracked closely before rising in the summer months, though still lower than the peak years. Now in October 2019 is again tracking close to 2018 as the coolest years in the North Atlantic.

This graph shows monthly AMO temps for some important years. The Peak years were 1998, 2010 and 2016, with the latter emphasized as the most recent. The other years show lesser warming, with 2007 emphasized as the coolest in the last 20 years. Note the red 2018 line was at the bottom of all these tracks. The short black line shows that 2019 began slightly cooler than January 2018, then tracked closely before rising in the summer months, though still lower than the peak years. Now in October 2019 is again tracking close to 2018 as the coolest years in the North Atlantic.

Walrus seem not brighter than buffalo, which American Indians tricked into stampeding over cliffs for feasting purposes.Buffalo were deliberately exterminated by the likes of William Tecumseh Sherman after the March Across Georgia.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike

There seems to be an evident warming trend about 0.3 deg per century. If we take only last part of the graph since middle seventies, we get a much bigger warming, over 2 deg per century – nevertheless, in this special case it is evident that the latter value has no foundation. Is the (often reported) sinister global warming concentrated to other parts of the globe?

LikeLike

Thanks udoli for commenting. You raise an important point. Several things to consider.

Note the graph at the top of the post is probably from a detrended dataset, showing the AMO phases without the long term secular rise from the end of the LIA. As Akasofu pointed out years ago, the global temperature record can be represented as a quasi-60 year oscillation on top of a steady increase recovering from the LIA.

https://i0.wp.com/venturaphotonics.com/sitebuilder/images/Fig48_ClimateModel3-600×348.jpg

Since the Kaplan dataset is not detrended and presents absolute temperature results, that background rise does appear, comparable to the 0.5C per century he estimated.

Of course there are other issues. As you note, there are warming and cooling cycles going on simultaneously in different parts of the ocean. One post here under the category “Oceans Make Climate” listed some of the major ones identified and under observation. Since the Ocean is a set of interconnected basins, changes in one place affect the others, both directly by water circulation and indirectly by atmospheric reactions.

Then there is the problem of comparing temp records from ship buckets and later engine intake boxes to today’s global drifter array. And the large disruption of the ocean water structure by wartime naval operations both WWI and II. So it’s tricky to put today in proper context to the past..

As oceanographers like to say: “It’s not that simple”. Dr. Whitehouse at GWPF has a paper out on just this point.

My focus is on the last 2 decades of more robust measurement technolgies (i.e. RAPID array, Argo buoys and the Global Drifter Network). I am wondering if the 1960’s are an analog for our decade soon ending, to be followed by a negative AMO phase.

LikeLike