We are witnessing the spectacle of a high-ranking Federal District Court Judge twisting the law to suit her empathy for climate activists. This is playing out as a lawsuit brought by Our Children’s Trust with kids as willing human shields in the “fight against climate change.” (Background resources at the end) The proceedings have gone on for several years with no end in sight unless a higher court stops it. The next segment is a long (50 courtroom days) hearing on the merits scheduled to begin October 29, 2018.

We are witnessing the spectacle of a high-ranking Federal District Court Judge twisting the law to suit her empathy for climate activists. This is playing out as a lawsuit brought by Our Children’s Trust with kids as willing human shields in the “fight against climate change.” (Background resources at the end) The proceedings have gone on for several years with no end in sight unless a higher court stops it. The next segment is a long (50 courtroom days) hearing on the merits scheduled to begin October 29, 2018.

The latest filings provide a view into how the legal system is being manipulated to support climatist beliefs and biases. The petition filed by the US is PETITION FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

Excerpts in italics with my bolds first from the federal defendants and later from the District Judge’s latest order (Respondents refers to the plaintiffs bringing the lawsuit)

From the US Petition for Dismissal:

With respect to standing, the district court concluded that respondents had adequately alleged injuries in the form of increased droughts, wildfires, flooding, and other effects of climate change, and that those injuries were caused by the government’s regulation of (and failure to further regulate) fossil fuels. App., infra, 125a-134a. The court further concluded that it could redress respondents’ alleged injuries by granting the relief sought, including ordering the federal government “to cease [its] permitting, authorizing, and subsidizing of fossil fuels and, instead, move to swiftly phase out CO2 emissions” and to “take such other action necessary to ensure that atmospheric CO2 is no more concentrated than 350 ppm by 2100, including to develop a national plan to restore Earth’s energy balance, and implement that national plan so as to stabilize the climate system.” Id. at 137a (citation omitted); see id. at 134a-137a.

On the merits, the district court concluded that respondents had stated a claim under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. App., infra, 137a-147a. Relying primarily on this Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015), as well as Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), and a 1993 decision from the Supreme Court of the Philippines, the district court found in the Fifth Amendment’s protection against the deprivation of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” U.S. Const. Amend. V, a previously unrecognized “fundamental right * * * to a climate system capable of sustaining human life.” App., infra, 142a; see id. at 140a-142a.

The district court further determined that respondents had adequately stated a claim under a federal publictrust theory. App., infra, 147a-167a. The court acknowledged this Court’s statement that “the public trust doctrine remains a matter of state law,” PPL Montana, LLC v. Montana, 565 U.S. 576, 603 (2012), as well as the D.C. Circuit’s rejection of a federal public-trust doctrine, see Alec L. ex rel. Loorz v. McCarthy, 561 Fed. Appx. 7, 8 (per curiam), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 774 (2014). But the court nevertheless concluded that a public-trust doctrine imposes a judicially enforceable prohibition on the federal government against “depriving a future legislature of the natural resources necessary to provide for the well-being and survival of its citizens.” App., infra, 148a (citation omitted).

The district court acknowledged the government’s arguments that “recognizing [respondents’] standing to sue, deeming the controversy justiciable, and recognizing a federal public trust and a fundamental right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life would be unprecedented,” but rejected the premise that the unprecedented nature of those decisions “alone requires * * * dismissal.” App., infra, 167a. The court expressed its view that “[f]ederal courts too often have been cautious and overly deferential in the arena of environmental law, and the world has suffered for it.” Id. at 167a-168a. The court invoked the “failure of the legal system to protect humanity from the collapse of finite natural resources by the uncontrolled pursuit of shortterm profits,” and stated that the “third branch can, and should, take another long and careful look at the barriers to litigation created by modern doctrines of subject matter jurisdiction and deference to the legislative and administrative branches.”

Respondents’ position amounts to the astounding assertion that permitting or encouraging the combustion of fossil fuels violates the Due Process Clause of the Constitution and a single district court in a suit brought by a handful of plaintiffs may decree the end of the carbon-based features of the United States’ energy system, without regard to the statutory and regulatory framework Congress enacted to address such issues with broad public input. Months ago, this Court flagged the “striking” breadth of those claims and the “substantial” doubts about their justiciability, reciting the standard for interlocutory certification and thereby indicating that appellate review is warranted before trial. United States v. U.S. Dist. Court, No. 18A65, 2018 WL 3615551, at *1 (July 30, 2018). But the district court nevertheless refused to meaningfully narrow respondents’ claims, to certify its orders for interlocutory appeal, or to halt the trial now set to begin in less than two weeks. The government therefore has no choice but to ask this Court once again to intervene— and to end this profoundly misguided suit.

In its most recent order, the court contemplates some of the “actions” that petitioners could take to redress respondents’ asserted injuries, including drastic measures like phasing out all greenhouse gas emissions “within several decades” or converting the Nation’s entire electricity generation infrastructure to “100 percent clean, renewable wind, water, and sunlight” sources. Id. at 54a (brackets and citation omitted). But neither respondents nor the court has cited any legal authority that would permit such an unprecedented usurpation of legislative and executive authority by an Article III court, essentially placing a single district court in Oregon—acting at the behest of a few plaintiffs having one particular perspective on the complex issues involved—in charge of directing American energy and environmental policy. Nor have respondents or the district court grappled with the fact that the carbon emissions arguably within the control of petitioners “may become an increasingly marginal portion of global emissions” as developing countries increase their own emissions, thereby making it all the more speculative and uncertain that even respondents’ unprecedented remedy would actually redress their asserted injuries.

Respondents’ suit is not a case or controversy cognizable under Article III. Respondents ask the district court to review and assess the entirety of Congress’s and the Executive Branch’s programs and regulatory decisions relating to climate change and then to undertake to pass upon the comprehensive constitutionality of all of those policies, programs, and inaction in the aggregate. See, e.g., Am. Compl. ¶¶ 277-310. No federal court, nor the courts at Westminster, has ever purported to use the “judicial Power” to perform such a sweeping policy review—and for good reason: the Constitution commits to Congress the power to enact comprehensive government-wide measures of the sort respondents seek. And it commits to the President the power to oversee the Executive Branch in its administration of existing law and to draw on its expertise and formulate policy proposals for changing existing law. Such functions are not the province of Article III courts. The district court’s contrary assertion constitutes a “judicial ‘usurpation of power.’”

From District Court Judge Ann Aiken October 15, 2018 Order:

This is no ordinary lawsuit. Plaintiffs challenge the policies, acts, and omissions of the President of the United States, the Council on Environmental Quality, the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Department of Energy, the Department of the Interior, the Department of Transportation (‘‘DOT’’), the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, and the Environmental Protection Agency (‘‘EPA’’). This lawsuit challenges decisions defendants have made across a vast set of topics—decisions like whether and to what extent to regulate CO2 emissions from power plants and vehicles, whether to permit fossil fuel extraction and development to take place on federal lands, how much to charge for use of those lands, whether to give tax breaks to the fossil fuel industry, whether to subsidize or directly fund that industry, whether to fund the construction of fossil fuel infrastructure such as natural gas pipelines at home and abroad, whether to permit the export and import of fossil fuels from and to the United States, and whether to authorize new marine coal terminal projects. Plaintiffs assert defendants’ decisions on these topics have substantially caused the planet to warm and the oceans to rise. They draw a direct causal line between defendants’ policy choices and floods, food shortages, destruction of property, species extinction, and a host of other harms.

This lawsuit is not about proving that climate change is happening or that human activity is driving it. For the purposes of this motion, those facts are undisputed.3 The questions before the Court are whether defendants are responsible for some of the harm caused by climate change, whether plaintiffs may challenge defendants’ climate change policy in court, and whether this Court can direct defendants to change their policy without running afoul of the separation of powers doctrine.

Unlike in the constitutional provisions at issue Nixon and Passman, the constitutional provisions cited here contain nothing approaching a clear reference to the subject matter of this case. The Constitution does not mention environmental policy, atmospheric emissions, or global warming. And unlike in Zivotofksy, climate change policy is not a fundamental power on which any other power allocated exclusively to other branches of government rests.

The question is not whether a case implicates issues that appear in the portions of the Constitution allocating power to the Legislative and Executive Branches—such a test would, by definition, shield nearly all legislative and executive action from legal challenge, Rather, the question is whether adjudicating a claim would require the Judicial Branch to second-guess decisions committed exclusively to another branch of government.

State-Created Danger Theory

Federal defendants urge that plaintiffs’ claims based on the state created danger doctrine must fail. First, they argue that plaintiffs do not show a special relationship between themselves and the government. More importantly, federal defendants argue that plaintiffs cannot show that government conduct proximately caused a dangerous situation in deliberate indifference to plaintiffs’ safety or that harm or loss of life has resulted from such conduct. Plaintiffs contend that they have proffered ample evidence to show genuine issues of material fact as to whether federal defendants have liability for the conduct alleged in their complaint.

Federal defendants’ main argument is that plaintiffs’ allegations regarding the government’s knowledge of the dangers posed to plaintiffs by climate change do not rise to the required level of “deliberate indifference.”Plaintiffs specifically refer to the declaration from their expert Gus Speth, former chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality under President Jimmy Carter. Mr. Speth’s declaration examines a historical record spanning ten presidential administrations and references a number of documents, statements of government officials, and federal policy actions that go directly to the government’s knowledge of the links between fossil fuels and increasing global mean temperature and the dangers associated therein, such as sea level rise to Americans at the time and in future.

For example, in 1969 Daniel Moynihan, then counselor to the President Richard Nixon, wrote to John Ehrlichman, President Nixon’s Assistant for Domestic Affairs, summarizing the climate problem:

The process is a simple one. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has the effect of a pane of glass in a greenhouse. The CO2 content is normally in a stable cycle, but recently man has begun to introduce instability through the burning of fossil fuels. At the turn of the century several persons raised the question whether this would change the temperature of the atmosphere. Over the years the hypothesis has been refined, and more evidence has come along to support it. It is now pretty clearly agreed that the CO2 content will rise 25 [percent] by 2000. This could increase the average temperature near the earth’s surface by 7 degrees Fahrenheit. This in turn could raise the level of the sea by 10 feet. Goodbye New York. Goodbye Washington, for that matter.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s science advisor Frank Press wrote to the President explaining: Fossil fuel combustion has increased at an exponential rate over the last 100 years. As a result, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 is now 12 percent above the pre-industrial revolution level and may grow 1.5 to 2.0 times that level within 60 years. Because of the greenhouse effect of atmospheric CO2, the increased concentration will induce a global climatic warming of anywhere from 0.5° to 5° C.

Injuries

Federal defendants argue that these declarations fail to show that plaintiffs’ injuries are concrete and particularized to them; rather federal defendants’ contend that the injuries alleged are generalized widespread environmental phenomena which affect all other humans on the planet, making them nonjusticiable.

The most recent Supreme Court precedent appears to have rejected the notion that injury to all is injury to none for standing purposes.”); Pye v. United States, 269 F.3d 459, 469 (4th Cir. 2001) (“So long as the plaintiff . . . has a concrete and particularized injury, it does not matter that legions of other persons have the same injury.”). Indeed, even if the experience at the root of [the] complaint was shared by virtually every American,” the inquiry remains whether that shared experience caused an injury that is concrete and particular to the plaintiff. Jewel, 673 F.3d at 910.

Causation

Plaintiffs submit evidence that fossil fuel emissions are responsible for most of the increase in atmospheric CO2, and that increasing CO2, in turn, is the main cause of global warming, and that atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses, due to fossil fuel combustion, are increasing quickly such that planetary warming is accelerating at rates never before seen in human history. Hansen Decl. Ex. A, at 38. Further, not only are concentrations of atmospheric CO2 continuing to increase, but the rate of increase has also nearly doubled since measurements began being recorded pushing humanity closer to the “point of no return.” Id. at 29, 38. Estimates show that extreme weather events are likely to continue to increase as the global surface temperature continues to rise. Id. at 35; Trenberth Decl. Ex. 1, at 1, 8, 13. Indeed, the five hottest years in the 123 years of record-keeping in the United States have all occurred in the past decade. Trenberth Decl. Ex. 1, at 3. Plaintiffs present evidence that 2017 saw record setting events such as extreme wildfires in the western United States8 and abnormally strong hurricanes in the southeastern United States and Gulf of Mexico (Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria), all of which were exacerbated by climate change. Id. at 7-11.

Further, plaintiffs offer that global sea level rise will continue unabated under current conditions. Plaintiffs’ expert Dr. James Hansen has submitted video animations showing how the future impacts of seal level rise will flood or impact the livability of the homes of plaintiffs in Louisiana, Oregon, Washington, Florida,New York, and Hawaii based on current assumptions about carbon emission. Hansen Decl. Ex. E-R. The most recent projections from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”) provide that global mean sea level will rise between 1.5-2.5 m (5-8.2 ft.) by 2100 and that it is expected to continue to rise and even accelerate more after 2100. Wanless Decl. Ex. 1 at 12.

In sum, the Court is left with plaintiffs’ sworn affidavits attesting to their specific injuries, as well as a swath of extensive expert declarations showing those injuries are linked to fossil fuel-induced climate change and if current conditions remain unchanged, these injuries are likely to continue or worsen.

Here, federal defendants argue again that the association between the conduct of which plaintiffs complain, namely the government’s subsidizing the fossil fuel industry; allowing the transportation, exportation, and importation of fossil fuels; setting of energy and efficiency standards for vehicles, appliances, and buildings; reducing carbon sequestration capacity and expanding areas for fossil fuel extraction and production through federal land leasing policies is tenuous and filled with many intervening actions by third parties. Thus, they argue that plaintiffs have failed to tether their injuries, both direct and indirect, to specific actions of the United States.

However, plaintiffs challenge not only the direct emissions of federal defendants through their use of fossil fuels to power its buildings and vehicles10, but also the emissions that are caused and supported by their policies. Plaintiffs have alleged that federal defendants’ systematic conduct, which includes “government policies practices, and actions, showing how each Defendant permits, licenses, leases, authorizes, and/or incentivizes the extraction, development, processing, combustion, and transportation of fossil fuel” caused plaintiffs’ injuries.

At this stage of the proceedings, the Court finds that plaintiffs have provided sufficient evidence showing that causation for their claims is more than attenuated. Plaintiffs’ “need not connect each molecule” of domestically emitted carbon to their specific injuries to meet the causation standard. Bellon, 732 F.3d 1142-43. The ultimate issue of causation will require perhaps the most extensive evidence to determine at trial, but at this stage of the proceedings, plaintiffs have proffered sufficient evidence to show that genuine issues of material fact remain on this issue. A final ruling on this issue will benefit from a fully developed factual record where the Court can consider and weigh evidence from both parties.

Remedy

Federal defendants contend that there is no possible redress in this case because the remedies sought by plaintiffs are beyond the Court’s authority to provide.12 Further, they argue that even if this Court did find in favor of plaintiffs, any remedy it fashioned would not redress the harms alleged by plaintiffs, because fossil fuel emissions from other entities would still contribute to continuing global warming. Thus, they argue that there is no evidence that any immediate reduction in emissions caused by the United States would manifest in a reduction of climate change induced weather phenomena. As the Court has stated before, whether the Court could guarantee a reduction in greenhouse gas emission is the wrong inquiry because redressability does not require certainty. Rather, at this stage, it only requires a substantial likelihood that the Court could provide meaningful relief. Moreover, the possibility that some other individual or entity might later cause the same injury does not defeat standing; the question remains whether the injury caused by the defendants in this suit can be redressed.

Instead, plaintiffs urge that their request for relief, at its core, is one for a declaration that their constitutional rights have been violated and an order for federal defendants to develop their own plan, using existing resources, capacities, and legal authority, to bring their conduct into constitutional compliance. Plaintiffs point to various statutory authorities by which they claim federal defendants could affect the relief they request.

The Court has considered the summary judgment record regarding traceability and plaintiffs’ experts’ opinions that reducing domestic emissions, which plaintiffs contend are controlled by federal defendants’ actions, could slow or reduce the harm plaintiffs are suffering. The Court concludes, for the purposes of this motion, that plaintiffs have shown an issue of material fact that must be considered at trial on full factual record.

Background

The Children’s Climate Lawsuit Harms The Children

Does the Constitution Provide a Substantive Due-Process Right to a Stable Climate System?

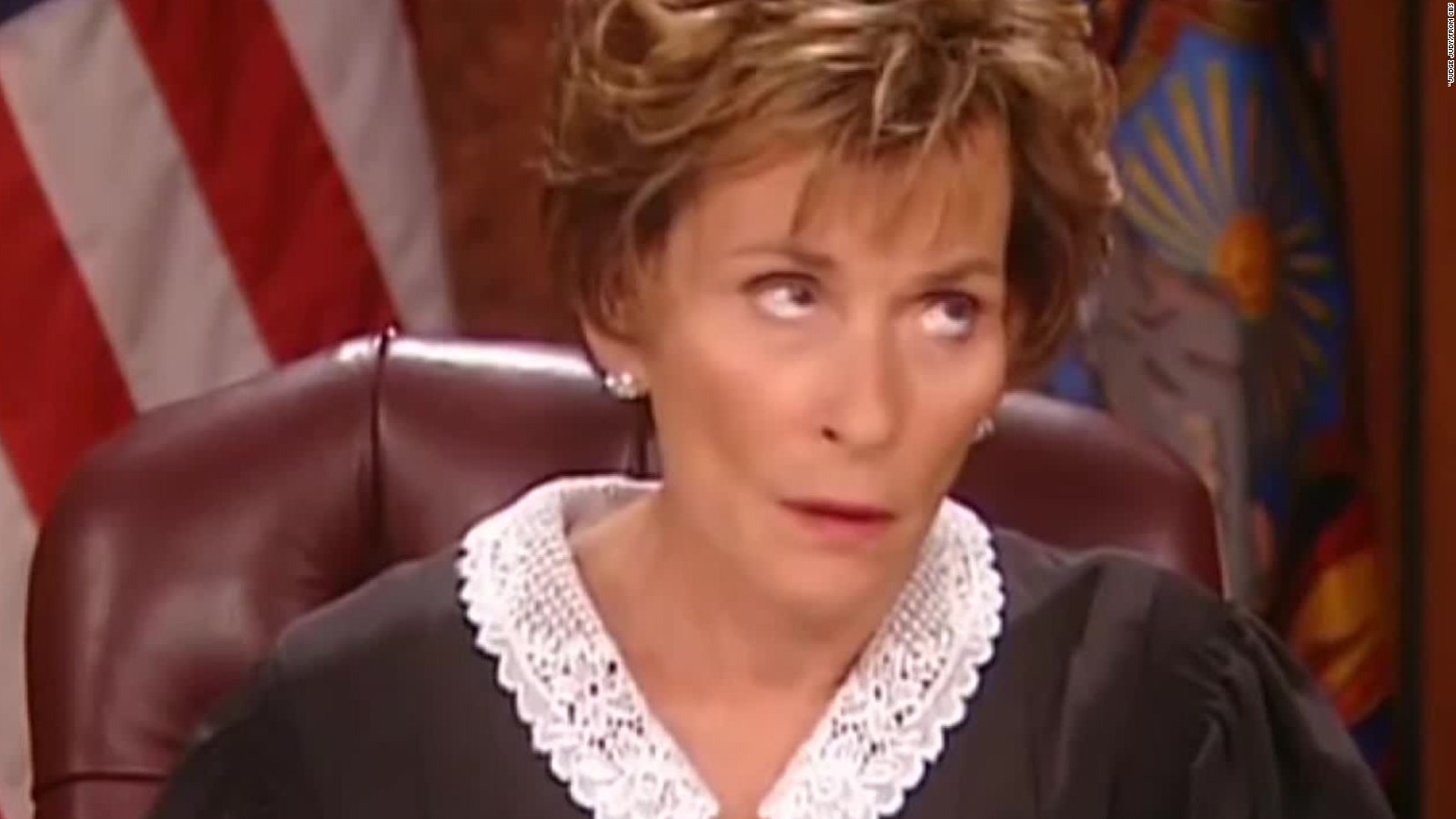

Judging objectively is not a sexist matter. Judge Judy proves women judges can be skeptical as well.

I would have responded more clearly: “alleged” would be in front of every claim the child manipulators put in their delusional laundry list in the reply.

I would have counselled to concede nothing in the response.

I would also seek sanctions against the lawyers for abusing the children named as plaintiffs.

They are straw plaintiffs, being cynically used by the climate extremists.

The motion in balance, however, is brilliant. It shows there are no damages, no connections, between the claims and reality.

Sort of like the relationship between reality and the consensus.

Great essay, thanks.

LikeLike

The judge’s “reasoning”, on the other hand, is so childish and shallow as to make a mockery of the law, due process and justice.

LikeLike