Update April 18 at End

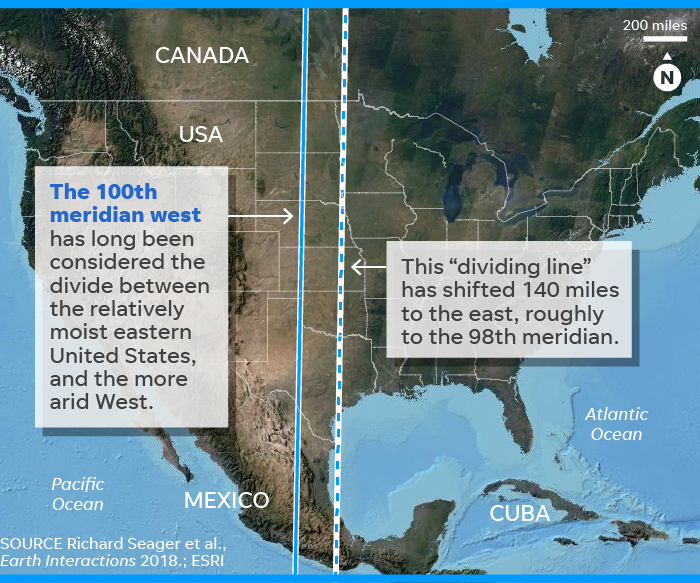

This latest alarm is about the eastward shift of the above climate zone boundary, which historically was located upon the 100th meridian. The narrative by alarmists is along the lines of “OMG, we are screwed because drylands are replacing wetlands. There goes our food supply.” Some of the story headlines are these:

As World Warms, America’s Invisible ‘Climate Curtain’ Creeps East

The arid US midwest just crept 140 miles east thanks to climate change

America’s Arid West Is Invading the Fertile East

A major climate boundary in the central U.S. has shifted 140 miles due to global warming

From USA Today

Both population and development are sparse west of the 100th meridian, where farms are larger and primarily depend on arid-resistant crops like wheat, the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies said. To the more humid east, more people and infrastructure exist. Farms are smaller and a large portion of the harvested crop is moisture-loving corn.

Now, due to shifting patterns in precipitation, wind and temperature since the 1870s — due to man-made climate change — the boundary between the dry West and the wetter East has shifted to roughly 98 degrees west longitude, the 98th meridian.

For instance, in Texas, the boundary has moved approximately from Abilene to Fort Worth.

According to Columbia University’s Earth Institute, Seager predicts that as the line continues to move farther East, farms will have to consolidate and become larger to remain viable.

And unless farmers are able to adapt, such as by using irrigation, they will need to consider growing wheat or another more suitable crop than corn.

“Large expanses of cropland may fail altogether, and have to be converted to western-style grazing range. Water supplies could become a problem for urban areas,” the Earth Institute said.

The studies appeared in the journal Earth Interactions, a publication of the American Meteorological Society.

What They Didn’t Tell You: Context Makes All the Difference

This is another example of misdirection to push FFF (Fear of Fossil Fuels) by ignoring history and human ingenuity, while kowtowing to climate models as infallible oracles. The truth is, we didn’t get here by being victims, and lessons from the past will serve in the future.

First, the West Was Settled by Adaptive Farmers

One of the best researchers and historians is Geoff Cunfer, who with Fridolin Krausmann wrote Adaptation on an Agricultural Frontier: The Socio-Ecological Metabolism of Great Plains Settlement, 1875-1936. Excerpts with my bolds.

The most important agricultural development of the nineteenth century was a massive and rapid expansion of farmland in the world’s grasslands, a process that doubled global land in farms. Displacing indigenous populations, European settlers plowed and fenced extensive new territories in North America’s Great Plains, South America’s campos and pampas, the Ukrainian and Russian steppes, and parts of Australia and New Zealand. Between 1800 and 1920 arable land increased from 400 million hectares to 950 million, and pasture land from 950 to 2,300 million hectares; much of that expansion occurred in grasslands. These regions became enduring “breadbaskets” for their respective nations and fed the nineteenth century’s 60 percent increase in world population. Never had so much new land come into agricultural production so fast. This episode was one of the most extensive and important environmental transformations in world history.

Most agro-ecologists and sustainability scientists focus on the present and the future. This article adapts their approach in order to understand agricultural change in the past, integrating socio-economic and physical-ecological characteristics that reveal both natural and cultural drivers of change. Socio-ecological profiles embrace land use, soil nitrogen, and food energy as key characteristics of agricultural sustainability. Ten descriptive measures link biophysical and socio-economic processes in farm communities to create socio-ecological profiles revealing human impacts on nature as well as environmental endowments, opportunities, constraints, and limitations that influenced settlers’ choices.

Tracing these characteristics from the beginning of agricultural colonization through sixty years reveals a pattern of expansion and growth, maturity, and adaptation. Agricultural systems are seldom static. Farmers interact with constantly varying natural forces and with social processes always in flux. The Kansas agricultural frontier reveals adjustments and readjustments to an ever-changing world and, especially, to environmental forces beyond settlers’ control. Three distinct socio-ecological profiles emerged in Kansas: a) high productivity mixed farming; b) low productivity ranching; and c) market-oriented dryland wheat farming. The following narrative addresses each profile in chronological order and from east to west across the state, revealing settlers’ rapid adaptation to environmental constraints; accompanying figures allow simultaneous spatial comparison.

Second, Farming was Sustained through Environmental Changes

Cunfer wrote a book On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment review here). Some excerpts with my bolds.

Though it may seem inconceivable to characterize the history of Great Plains land use as stable, Cunfer uncovers a persistent theme in his research: Great Plains farmers surprisingly found an optimal mix between agricultural uses (in particular, plowing vs. pasture) quickly and maintained this mix within the limits of the natural environment for a surprisingly long period of time. Only occasionally, in particular during the mid 1930s, did farmers push the boundaries of this regional environment; however, they quickly returned to a “steady-state” land-use equilibrium.

In particular, Cunfer blends together these two extreme approaches and summarizes Great Plains agricultural history in three components: (1) the rapid build-up of farm settlements from 1870-1920, which substantially altered the surrounding environment; (2) relative land-use stability from 1920 to 2000; and (3) the occasional transition in agricultural techniques which resulted in a quick shift away from this land-use equilibrium.

The Dust Bowl still remains an important environmental crisis and it is often a rallying point for federal government conservation programs. Cunfer adds to this literature by applying GIS maps to the entire Great Plains and interpreting comparative sand, rainfall, and temperature differential data to conclude that “human land-use choices were less prominent in creating dust storms than was the weather” (p. 163).[1] The localized portion of the Great Plains where dust storms were magnified contained substantially more sandy soil, only a small percentage of land devoted for crops, and the greatest degree of rainfall deficits from past trends. This non-exploitative argument contradicts the conventional wisdom which maintains that a massive plow-up followed the trail of increasing wheat prices and low cost of farming.

Our Ancestors Prevailed and We have Additional Advantages

Just as pioneer colonization inscribed a new cultural signature onto a plains landscape constructed by Native Americans, industrial agriculture began to over-write the settlement-era landscape. Fossil fuel-powered technologies brought powerful new abilities to deliver irrigation water, apply synthetic fertilizers, control pests, and reconstruct landscapes with tractors, trucks, and mechanical harvesters. A new equilibrium between environmental alteration and adaptation emerged. Industrial agriculture’s remarkable ability to alter and manage natural systems depends on a massive mobilization of fossil fuel energy. But until the early twentieth century farmers accommodated and adapted to natural constraints to a considerable extent.

Fig. 1 An energy model of agroecosystems, optimized for estimation based on historical sources (adopted from Tello et al. 2015)

Summary

It is disrespectful and demeaning for the activist media types to pretend we are unprepared and incapable of adapting to changing environmental and climate conditions. Present day knowledge of agroecosystems is highly advanced, supported by modern technologies and experience with crop selections and choices for diverse microclimates. Confer and colleagues discuss the possibilities in a paper Agroecosystem energy transitions: exploring the energy-land nexus in the course of industrialization

A previous post at this blog was Adapting Works! Mitigating Fails. discussing how farmers pushed the extent of wheat production 1000 km north through adaptation and innovation.

Warming has produced bumper crops most everywhere.

Update April 18

Dr. Roy Spencer has also weighed in on these scare stories, and adds considerable perspective. He challenges the claim that the eastward shift has happened.

Since I’ve been consulting for U.S. grain interests for the last seven or eight years, I have some interest in this subject. Generally speaking, climate change isn’t on the Midwest farmers’ radar because, so far, there has been no sign of it in agricultural yields. Yields (production per acre) of all grains, even globally, have been on an upward trend for decades. This is fueled mainly by improved seeds, farming practices, and possibly by the direct benefits of more atmospheric CO2 on plants. If there has been any negative effect of modestly increasing temperatures, it has been buried by other, positive, effects.

And so, the study begs the question: how has growing season precipitation changed in this 100th meridian zone? Using NOAA’s own official statewide average precipitation statistics, this is how the rainfall observations for the primary agricultural states in the zone (North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma) have fared every year between 1900 and 2017:

What we see is that there has been, so far, no evidence of decreasing precipitation amounts exactly where the authors claim it will occur (and according to press reports, has already occurred).

Spencer’s post is The 100th Meridian Agricultural Scare: Another Example of Media Hype Exceeding Reality

Excellent debunking of those terrors that work on the assumptions that the climate and weather was totally static until man started interfering and we cannot adapt to any changes or conditions. As you know we ran out of raw materials, petroleum and food 4 decades ago and most of us died in the ensuing wars for the remainder.

LikeLike

Bob, I was with you until the final sentence. I think you should lay off the Hunger Games books and movies for awhile.

LikeLike

Hunger Games? Try the Population Bomb and all dire scenarios spinning off from that circa 1970. Some of it included the rapid coming of the next ice age. In the early 70’s I had a Professor of Meteorology explain that the glaciers were soon to start moving south at better than a mile per day. Solid science and, as you know, you just can’t dispute science from a scientist.

Hunger Games seems to have some of that gloom and doom, but I’m remembering stuff I read and heard about 50 years ago.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike